Week 7. Carbohydrate (‘Plant Based’) Sports Nutrition for Maximum Performance and Health.

The Science of Adjusting Amount of Carbohydrates for the Couch Potato, the Endurance Athlete, and Everyone Inbetween

When it comes to endurance training or ‘cardio’ training do you truly understand how to adjust training intensity for increasing your own or client’s ability to run, bike, or row at the fastest speed over time that will not result in overtraining or lead to exhaustion or injury?

What if you or they are training merely to run/finish a race not competitively, but to feel strong, healthy, and just be able to get out and perform or participate in physical events at any time – as opposed to a one-time potentially (and commonly) stressful and draining event?

How do you train yourself or them to work ‘hard’ intelligently? What does working ‘hard’ mean?

The transition from ‘just the right dosage’ to ‘too much’ occurs very quickly over a very small increase of speed or intensity – and coincides with the need to eat either a lower or substantially greater carb intake.

This presentation begins examining the athletes in two sports that require the highest carb intake – the pinnacle of high carb requirements. From this ‘pinnacle’ of high carb intake, we breakdown carb requirements progressively to lower amounts and define what justifies a ‘proper’ carb intake for all humans relative to any activity level.

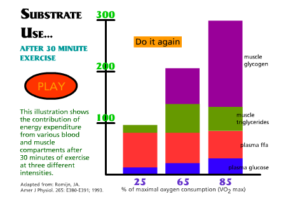

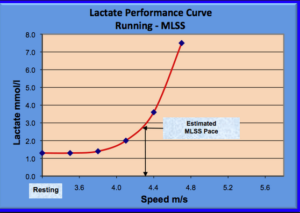

The area to the right of the red line is marked ‘HIGH CARB’ because of the extremely high rates of glycolysis and acid production. The problem with extreme acid production however, is that it severely limits the time exercising in the red zone, which means exercising at high intensity for very brief times do not necessitate eating a high carb diet. Total time ‘how you live/what you do’ on either side of the red line is what really matters. However, very small changes in intensity just above the circled spot begin to severely limit the time to do ‘stuff’ or exercise. It’s these small changes we want to understand, which cause big changes in both nutritional intake and how your body adapts to exercise. The circled spot is technically called the ‘inflection point’ on the blue line of the graph. The red line drops down from the inflection point merely to identify the intensity and set the optimal speed for competing in a long distance race. Once you see how optimal ‘max-speed’ is maintained then you can see how Maximal High Carb Intake is set and why it exists. So first we look at ‘How to Set Optimal Speed’ – next!

This section is the sister material to Week 14: Visualizing Cardiac Output and Blood Flow Physics; Section C: Tapping Out the Full Potential of Your Aerobic Capacity is Limited by Lactate Threshold.

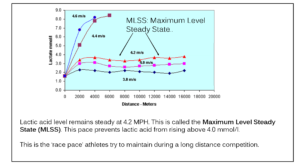

The key to maximizing a constant speed or intensity over time demands one thing: not working excessively hard – with the expressed purpose to limit acid production. This is where measuring acid-lactate levels during exercise becomes important, shown below. Race pace occurs when acid levels remain limited and steady – below 4mmol/L – the red line in this graph. BREAK: See Visualizing Lactate Threshold in Workbook, Week 4 For nutritional purposes, knowing the maximum intensity that can be sustained over time is the key for knowing how to ‘cut down on carbs’ – for any sport, activity, or lifestyle. To start, we look at the two training methodologies and sports where athletes maximize glycolysis and high acid production over time, typically in a period from 2 to 3 hours – next section.

METHOD 1 – Maximal Steady State Training. The red line in the graph below shows the maximum speed running where acid production stays constant – just below 4 mmol/L. 4.2 m/s is the maximum speed tolerated before the spike in lactate occurs. This maximum speed is called MLSS: Maximum Lactate Steady State. This person’s MLSS occurs running 4.2 m/s and is sustained for 16,000 meters, which covers almost 10 miles running 9.4mph steadily. This is a very fast pace; it equates to running a 2:47 marathon. MLSS Pace on a ‘regular acid graph’ below is estimated by ‘eyeball guessing’ what’s called the inflection point. Simply mark the spot where the acid-lactate level start increasing exponentially. Note the similarity with the spot I circled on the first graph at the very top of this page. The black arrow points from the inflection point to the ‘race pace’ speed – a bit slower than 4.4 m/s – which of course coincides with the MLSS in the top graph. METHOD 2 – Interval Training: Perform briefly at intensities where glucose utilization and acid production are very highly spiked. Repetitive bursts of high intensity provide another way to deplete great amounts of glycogen. You must rest, do nothing, or perform very easy exercise between the bursts. Intervals can be performed through totally seemingly different types of exercise. For example, consider the similarity between running and weight training – specifically the 400m dash and performing Leg Presses in a gym. 1. 400m dash: Mostly legs power the motion up to 50seconds at the finish- failure to maintain power. The 400 m world record time is 43.03 seconds. Held by Wayde van Niekerk 2. Leg presses – from 15-20 reps: Takes up to 50 seconds to reach failure. Both approaches rapidly deplete glycogen. Thus, the nutritional requirement for recovery – carbohydrate wise – is essentially identical. Below are two prototypical athletes who train or perform above the red zone – although in two different ways. Both sports above require maximizing carb intake in order to replete glycogen stores. The above athletes require Max Carb Intake. From this ‘pinnacle’ we breakdown the method for cutting carbs progressively – from the maximum intake to the lowest levels – for optimal fitness and performance. So how do we calculate Max Carb Intake in terms of grams of carbs needed to replete glycogen? Cheat. Learn How to Use the Cheat Sheet Method, next section.

Multiply body weight (in kg) by the gram counts of carbs (CHO, how much) EXAMPLE CALCULATION: Maximal Carb (CHO) Intake Consider a 70kg male (154lb) top endurance athlete: However, even top endurance athletes must cut ‘maximum carb intake’ when they reduce time performing. Thus, we proceed by cutting carbs progressively from the maximum amount to cut carbs to the ‘correct’ amount for all other conditions. Who Needs the Max Carb Intake of 603g? Cut #1: From Max time in Glycolysis to Moderately High Intensity Steady State Training. Cut #2: Down to Low Intensity Steady State Training (and Pure Strength Training). Not low at all in the view of people who understand how the body works. Cut # 3: Little or No Exercise – Lowest Amount of Carbs. Again, not low at all in the view of people who understand how the body works.

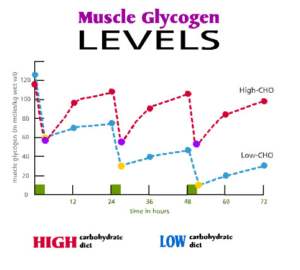

To begin, we look at a landmark study by David Costill that established Max Carb Intake in humans. First, realize the classic Costill study of elite cyclists (graphed below) was a contrived and rare event, purposely designed to force extreme glycogen depletion. This study required trained cyclists to repeat 2 hours of intense exercise 3 days in a row. Practically nobody performs repeated bouts of extreme red zone level activity unless: Thus, a precedent for Max Carb Intake was established @ 587 grams. Compare this way of obtaining Max Amount of 587 grams of carbs (or 2,348 calories) to the ‘Max Amount’ from the cheating table in the previous section. We had calculated 630 grams of carbs, which = 2,520 calories. Only certain competitive athletes from a few sports and a handful of obsessive endurance racers train and compete in extreme ways. This time we do not cut carbs using the cheat sheet. Instead, we look at directly at how reducing intensity and time reduces glycogen depletion, which therefore decreases carbs needed for repletion. Like the cheat sheet reductions, I list the cuts in carb intake in a progressively descending way from Max Carb Intake. Trial 1 is the first cut. It cuts the ‘Max Amount’ of 587 grams of carbs obtained from the cyclists in the Costill study who fully repleted glycogen levels after 2 hours of very intense exercise. This cuts the cyclists’ time performing from 2 hours to 1 hour, but maintains the same intensity. Because time is halved we assume glycogen depletion is halved, thus we cut carbs in half. Compare the 294g of carbs to using the cheating table method: halving 9g/kg to 4.5g/kg – for a 70kg man. Perform again in a 1hr bout, but reduce intensity. The effective drop is shown by comparing the glycogen depletion in the middle bar to the right bar in the graph below. It is approximately 50% less. So, 294g must be lowered. Let’s be conservative again and say the repletion amount is slightly more than half of trial one’s total of 294g – say 55%. Cut the trial 2 amount in half. COMPARE the 81g of carbs day to the previous section’s calculation for little to no exercise: 1. Indisputably, low rates of glycolysis spare a person’s glycogen stores. 2. Sports that require exerting absolute maximum strength for very short periods of time overall – or athletes who are very mechanically efficient and never exhaust themselves – do not require max carb intakes and maximal glycogen levels in their muscles for performance. 3. It is not necessary to have full muscle glycogen stores to perform at full strength. Consider thoughts of this martial artist who answers the question on why he purposely does not replete glycogen after workouts. “I don’t actually top it off every workout. I try to maintain just enough to keep me going during each workout. If I have a really long session coming up (sometimes I’ll be doing stuff for hours and hours with my friends on weekends) I might shoot for supercompensation, but that’s mostly for giggles.” 4. There is no reason to eat a high carb diet to top off muscle glycogen ever – especially if you don’t plan on performing lots of ‘reps-exhaustion’ exercise. 5. Many sports nutrition charts are geared to fully replete glycogen – which is necessary only for repeating extreme performances. 6. People who ‘exercise regularly’ may easily eat excessive amounts of carbohydrates, since they may think the exercise they do requires it. Ultimately, the only thing that determines the need for a high carb diet is total time performing at high or exponentially high rates of glycolysis. Simply adjust intake to your current regimen. You must not be afraid to increase fat and protein levels when carb intake should be low. Costill and others laid down a holy grail for non-athletes competing in marathons and such to practice high carb recovery nutrition as if they trained like Tour de France riders – for example, by piggin’ out on pasta the night before an endurance race. Legions jumped on the bandwagon, and many have remained on it since. Famous authors like Professor Tim Noakes (writer of the Lore of Running) taught legions of runners to maximize carb intake after running or after ‘aerobic exercise’. However, Noakes has since changed his mind as a result of developing ‘prediabetes’. Read on that here. Forcing the body to ‘recover’ by fully restoring muscle and liver glycogen may stress the organs (pancreas and liver mainly) doing the work. Eating 800 to 1000 grams of carbs/sugar a day to force maximal glycogen repletion means the pancreas must secrete insulin constantly and often in high amounts. Now, if you’re an athlete who must repeat a performance, then yes, you must ‘overfeed’. But assuming you are not trying to repeat high intensity exercise in consecutive days, there definitely is no need to force full repletion. It just may be healthier to avoid refilling glycogen levels as fast as possible and take a few days as opposed to making it happen in 24 hours.

[HR] MLSS is the essential dividing line for improving fitness for the body to compete in endurance events and for determining the need to eat a low or high carb diet. Indisputably, low rates of glycolysis spare a person’s glycogen stores. There is no reason to eat a high carb diet to top off muscle glycogen ever – especially if you don’t plan on performing lots of ‘reps-exhaustion’ exercise.

1. Who Needs High Carbs? / Who Needs Low Carbs?

The foremost factor that determines the need for a maximally high or very low carb carb diet is the total time performing at very high rates of glycolysis.

2. How to set ‘Optimal Speed’ for an athlete to sustain maximum speed over the entire distance of a long race.

Maximizing an optimal constant speed over distance is called race pace.

3. Two Exercise Methodologies (and Sports) that Maximize Glycolysis and Acid Production over Time.

Which athletes classically perform steady state or interval style?

4. The Cheat Sheet Method for Cutting Carbs

Who?

How Much?

Individuals who exercise regularly

4.5 – 6.0 CHO g/kg BW/day

Intermittent, power, strength or sprint sports

5 or more CHO g/kg BW/day

Endurance sports (aerobic training>90 minutes a day most days of the week)

8 – 10 CHO g/kg BW/day

Source: http://btc.montana.edu/olympics/nutrition/eat10.html – MSU no longer provides this info.

Begin cutting carbs progressively from the Max Carb Intake: 630g

5. Cutting Carbs for Health and Performance: A Scientific Method to Adjust Carb Intake for All Athletes

— five Ironman-length races in five daysThe cyclists in the High CHO (carb) group ingested an average of 587 grams of carbs to fully replete glycogen within 24 hours.

Extreme performances which demand Max Carb Intakes are rare events for most humans.

Cutting the Carbs Progressively According to Reduced Glycogen Depletion:

TRIAL 1. Cut time by 50%.

TRIAL 2. Cut intensity of Trial 1.

Now, 294 grams/day is excessive.

Now, 294 grams/day is excessive.

TRIAL 3: Little to no exercise.

Six Takeaway Messages

SUMMARY:

6. Training Methodologies Placed on a Lactate Graph

Only people who train at Steady States near MLSS or Intermittently Above MLSS for appreciable amounts of time need to eat high carb diets.

Primary Concepts: Talking Points

1. Max Carb Intake is only necessary for:

a) Training near or at Maximum Lactate Steady States (MLSS)

b) People like hockey players who perform repetitive ‘sprint bursts’ (intervals) throughout an entire game or practice.

2. From the pinnacle of Max Carb Intake, we ‘cut the carbs’ progressively.

This is a functional based carb intake specific to activity level or lifestyle for all humans.

3. To train for competitively (to increase race pace speed) train near, at, or slightly above lactate threshold.

a) Find Maximum Lactate Steady State, then sustain MLSS aka race pace to run ‘forever’.

Getting faster and running at a greater fraction of your VO2 max is another challenge entirely – as shown in Week 14, Section C5. (Advanced Strategies for Endurance Training)

b) Develop a feel for performing at the intensities or paces where you’re at Lactate Threshold. Heart rates also provide a gauge, but knowing your speed is more important.

4. Weight training or resistance exercise – reps/exhaustion style – is a form of interval training.

a) A 400m dash is similar to performing leg presses – from 15-20 reps to near failure.

b) Overall glycogen depletion can be moderately high to high when reps/exhaustion schemes are performed. (Glycogen depleting workouts).

5. Pure strength training – neural recruitment, heavy weight/low reps – does not deplete as much glycogen as reps/exhaustion training.

a) Dependent on mechanical efficiency, skill, and knowledge of self – a lower carb diet is ‘smart’ for staying lean and strong – as long as the focus is truly on neural recruitment.

6. Why has a plant based diet always been the base for the diet in athletes or most humans (including avid meat eaters)?

– discuss in class

Fantastic goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you

are just extremely great. I really like what you’ve acquired here, certainly like what you’re saying

and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still care for to keep it wise.

I cant wait to read far more from you. This is really a tremendous website.