The Physical Rules

of the Heart, Blood Flow, and Cardiac Output

The Case for Speed

How to Build Your Marathon Muscles

How to Build Your Marathon Muscles

While we all run at different paces and in different places, many of us share a common goal — to get faster. It might be faster than your buddy, or faster in your next race, or even faster than yesterday? But the minute you hit “stop” on your watch it’s running human nature to start doing the math on how you can improve. Problem is, with so many programs promising fast gains, the vast majority of runners don’t conceptually know how to begin getting faster. Should you run longer? Should you cap your heart rate? Do you need to go faster? Is it the shoes? The answer, actually, is closer than you think: if you want to become a faster runner, you need to focus on the pace your running muscles can sustain.

The Heart of the Problem

If you are like 80 percent of the runners on the road today, you own and use a heart rate monitor to guide your training. If not, you have probably seen the color-graded chart of exercise intensity on the wall of your local YMCA or gym, encouraging you to hit a target heart rate for specific exercise benefits.

Contrary to popular belief, cardiovascular fitness is not a good marker of running fitness or even running performance. While it’s better than nothing at all, it’s deceptive in that many runners are lead to believe that their Heart Rate is an indicator of their fitness. Heart rate looks only at the stress on the cardiovascular system–or to paraphrase, what your muscles are demanding of your body. As such, Heart rate is removed from the central proposition of your training — how hard your muscles are working. Add to this the fact that HR is also influenced by factors like dehydration, heat and stress.

In fact, you can gain fitness with no change in HR; you can have different HRs for multiple repeats of the same test and still have not gained any fitness. For more information in this area, you can refer to the following resources: VO2, Lactate Threshold, VO2max, and Endurance Performance, Hagberg, J. M. (1984). Physiological implications of the lactate threshold. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 5, 106-109; and Maximal Oxygen Consumption – The VO2max.

Your Running Muscles

The easiest way to understand this concept is just this: your muscles are what power you around the block to a five-mile personal best effort–Not your heart.

Your heart tells you how hard your body is working, but the only thing that can make you faster on your next attempt at that run is stronger legs.

Inside Marathon Nation we measure your functional running fitness via a 5K test so we can get your pace for that effort.

We then use that effort, the one you physically did (not from a chart), to map out your training intensities across the program. This leads to focused workouts that are essentially personalized to your current proven fitness levels.

Pace is a better gauge of intensity because it directly relates to muscle loading or motor unit recruitment (muscle work).

An 8 minute/mile is the same effort in your neighborhood as it is on race day.Try pegging your run pacing to a specific heart rate and you could be doing a 5 mile loop at 8:30s one day and 7:30s the next. There’s simply no consistency.

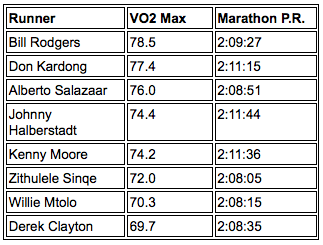

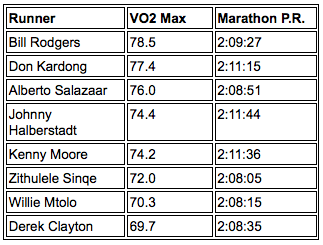

In fact, at the intensities that we race (from the 5K to the marathon), the pace at threshold is a much more useful marker. Exercise physiologists have begun to note that many training programs result in improved performance, but do not improve VO2 Max significantly. This has led many to shift from using VO2 Max as a marker of fitness to using power/pace at lactate threshold. As it turns out, VO2 max seems to be a rather poor predictor of endurance performance. Consider the following examples:

Note that Derek Clayton ran a faster marathon than Don Kardong, despite having a significantly lower VO2 Max. If the cardiovascular system adaptations were the most important determinant of how fast you go, VO2 max would tell the whole story?but it doesn’t. The biggest VO2 max does not always win.

If Running Is Muscular, How Do We Think Muscles?

If running a 20-minute 5K is a set unit of work, or fitness, then being able to do that same course in less time (i.e. do more work) means you are now fitter. To run faster we need stronger muscles or more of them. When we get this granular, then it’s easy to see how every training session is nothing more than an opportunity to recruit more motor units.

The more you activate a motor unit, the more it begins to take on slow-twitch characteristics. In fact, it has been shown in laboratory mice that chronic electrical stimulation will convert the plantaris muscle from 90 percent fast-twitch to 90 percent slow-twitch. As you increase the intensity of the average training session, you recruit all of the slow-twitch fibers and begin to recruit fast-twitch. Each flavor of muscle cell becomes better and better at what they do. The slow-twitch fibers become really good at being slow-twitch fibers. Fast-twitch fibers begin to take on the characteristics of slow-twitch fibers: they can go longer and burn fat for fuel. The net result is that your capacity for work will increase: slow-twitch fibers become better and stronger at what they do, and they increase in number.

In order to make this work, however, you need to do a significant amount of moderate or high intensity work so as to recruit intermediate and fast-twitch fibers, causing a shift in their characteristics towards slow-twitch. These muscles will, in turn, produce less lactate and improve their fatigue resistance, driving up your lactate threshold and sustainable pace. In other words, all this work will make you into a faster runner.

How Does This Change Your Training?

The popularity of less-is-more programs has grown in the last few years. While not all of them are good, most are way better than the traditional long-slow-distance approach that just counted on you accumulating miles at a set (low) aerobic effort. This volume-oriented approach does work, but it requires so much volume that either the average John/Jane Doe (A) doesn’t have time for it or (B) won’t be able to physically survive the miles. Her are a few suggestions to revamp your plan to make the most of the training you are doing.

- Benchmark Your Fitness?Schedule a 5K time trial run on a local, flat course. Do your best and use the resultant time and pace per mile to shape the rest of your training. Even if you don’t get that granular with the data, regular testing every 4 to 6 weeks will give a good indication if your fitness is improving!

- Weekly Intensity?Don’t be afraid of intensity, especially in smaller doses. The standard Marathon Nation Training Week has both Tempo and Interval training sessions. A great example is 4 to 6 repeats of 3 minutes each at 5K pace, with 2 minutes of recovery. By the end of your workout you’ll have almost racked up a 5K of solid work without too much fatigue.

- Smart Long Runs?Make those long slow runs a thing of your past by cutting the volume by 2/3 and adding intensity to the run. A 15 mile long slow run can quickly become a 10 to 12 mile effort as 4 miles easy, 6 miles at marathon pace, 2 miles at half marathon pace (or as fast as you are able). By the time you are done, you’ll have done more “work” than the standard easy run and you’ll be done faster! Save those uber long runs for a race simulation or for your final training peak.

- Improved Recovery?More more work means more rest, period. Don’t fall victim to thinking your new fast-self is immune?running harder is actually harder on our bodies. From self massage to weekly stretching to two days off a week to post-run ice baths and recovery shakes, how you absorb the work is just as (if not more!) important than the work itself.

5k Race, Runner’s True Test

5k Race, Runner’s True Test

Published May 25, 1998, in The Post-Standard. By Dr Kamal Jabbour, Contributing Writer

Every weekend, the race calendar contains one or more local 5K races. Charity events and fun runs feature 5K races. The distance of 5 kilometers, or 3.1 miles, is short enough to walk within an hour, yet long enough to give it some legitimacy as a distance event. As a result, the 5K road race has become an integral part of the American running scene.

A beginner’s first race is almost always a 5K. Many seasoned runners stay away from 5K races, preferring the endurance of the longer distances. In doing so, they miss out on what may be the true fitness test of running.

Running relies on a mix of aerobic and anaerobic energy to achieve optimal performance. Short sprints rely almost entirely on anaerobic power, while marathons use pure aerobic energy. A runner’s pace decreases as the distance of the race increases. As a result, long distance events are contested at a fraction of a runner’s all out pace, and use only a portion of the runner’s maximum aerobic capacity.

Maximum aerobic capacity VO2max is measured in milliliters of oxygen consumed per minute per kilogram of body weight. In his landmark book on sports physiology, Inside Running,

Dr. David Costill reported that runners use close to 100 percent of their VO2max when running a 5K race, about 85 percent for a 10-mile race, but require only 70 to 80 percent of VO2max when running a marathon.

Ed’s comment: The above numbers relate to WINNING times of elite runners. Running 85% of VO2 max in a marathon matches the world record in the lactate graph below:

Thanks on your marvelous posting! I really enjoyed reading it, you

happen to be a great author.